Word Clock

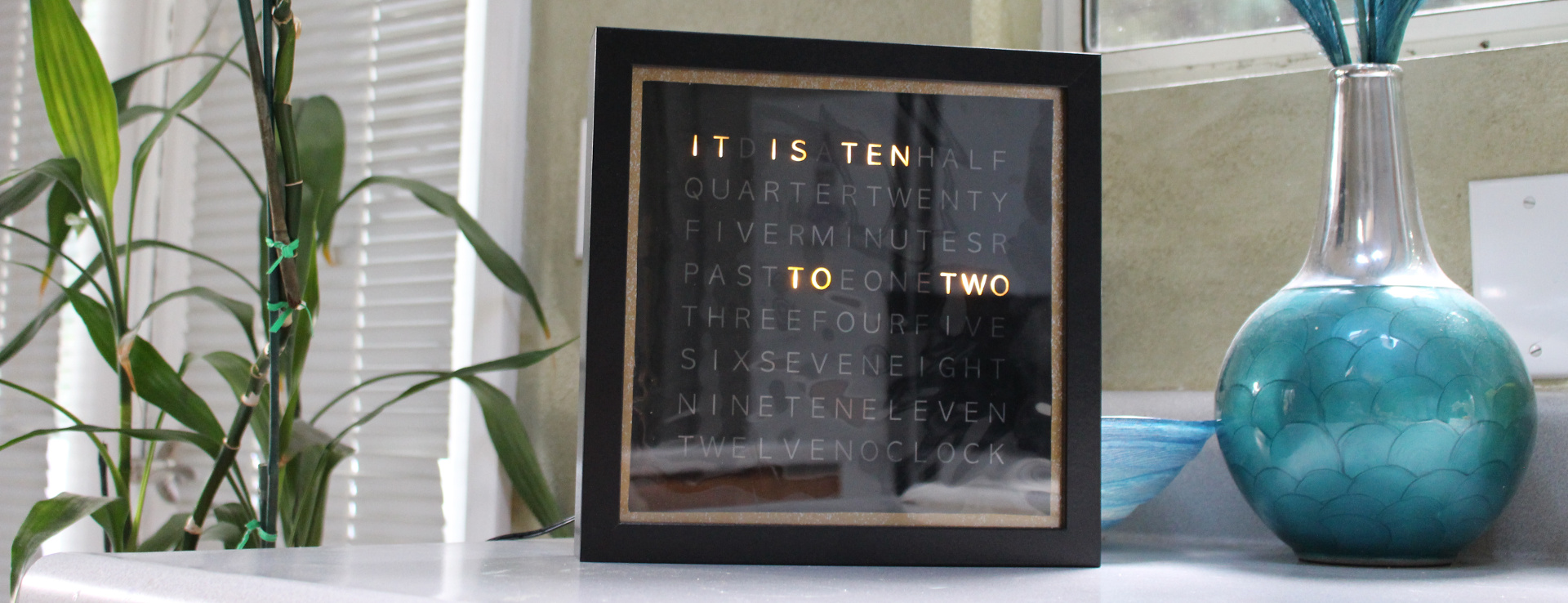

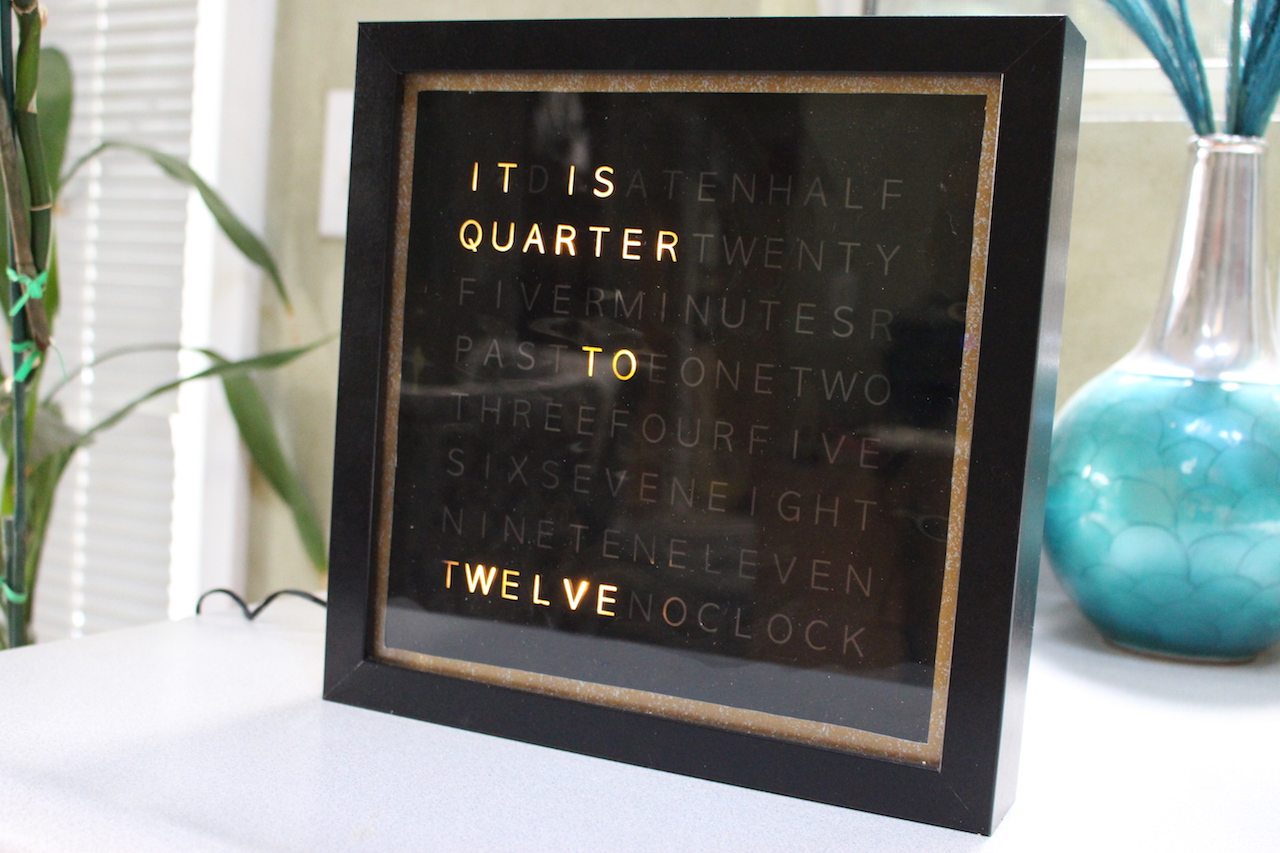

A word clock communicates the time with letters rather than numbers or hands.

I made this one as a Christmas gift for my dad in 2016. This post is a high-level retrospect of its development; the schematic, parts list, and firmware are linked toward the end.

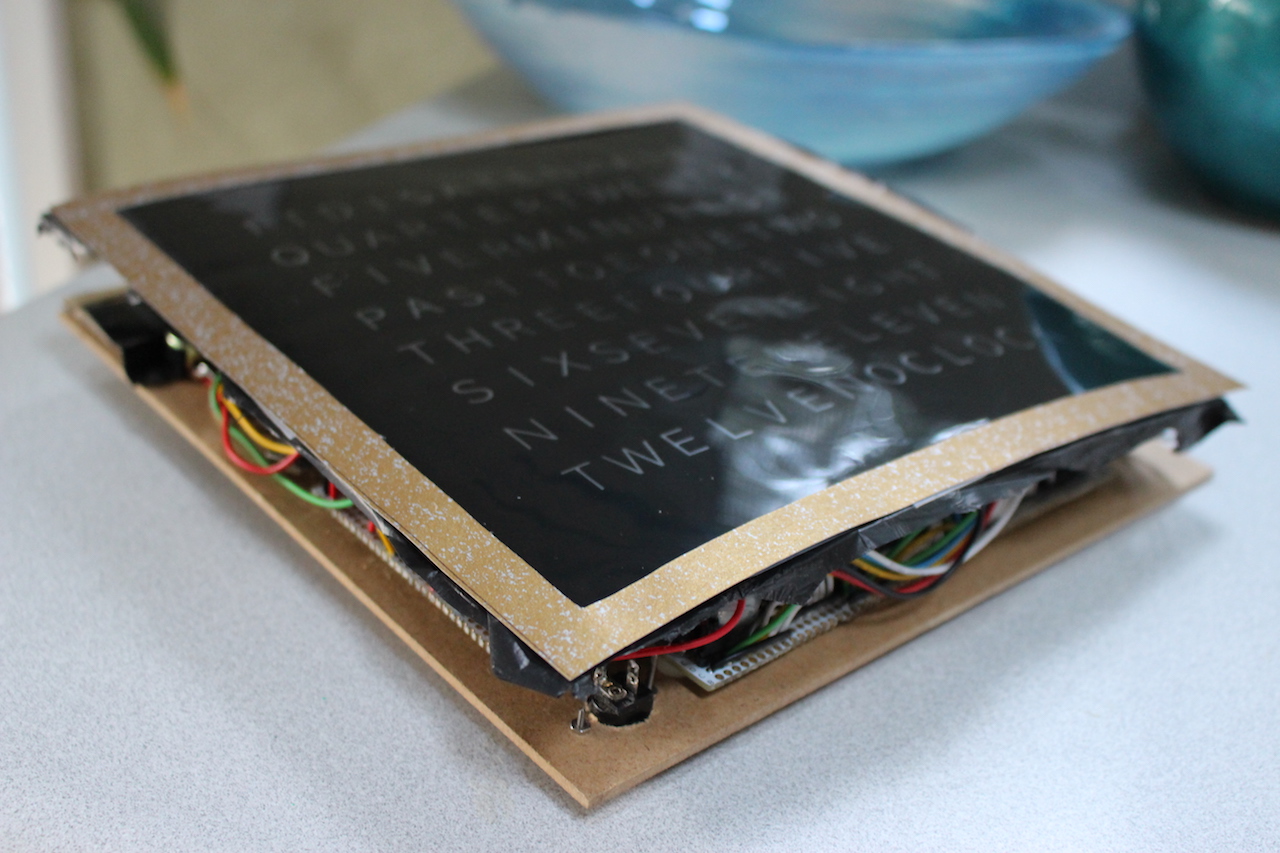

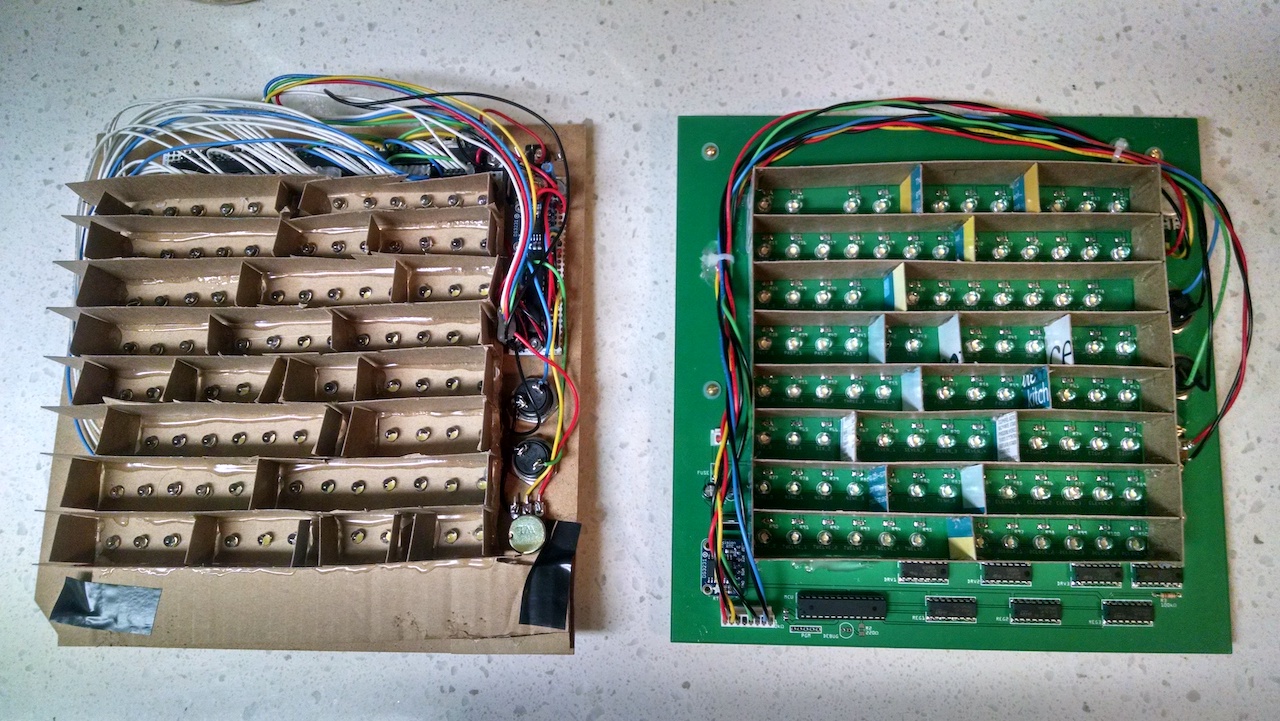

Before going too far, I want to point out that this turned out to be a beta build. I wound up with a rat’s nest of wires, crammed components, and light bleeding through the baffles. It was a good proof of concept, but I took what I learned and made a second version with a custom PCB, and the results were way better. See Addendum.

Overview

- Tech: ATMega328P + DS3231 + 98 5mm LEDs

- Chassis: IKEA Ribba shadow box

- Build date: November - December 2016

Design

The word clock is a popular project among electronics hobbyists. It’s taken many different forms.

To me, its appeal is its elegance. It’s colloquial and casually imprecise, but accurate enough for most needs.

I thought scottbez1’s instructable captured that philosophy well, so I based my design heavily on his. Some of this repeats his work, but I made changes along the way.

Letter Mask

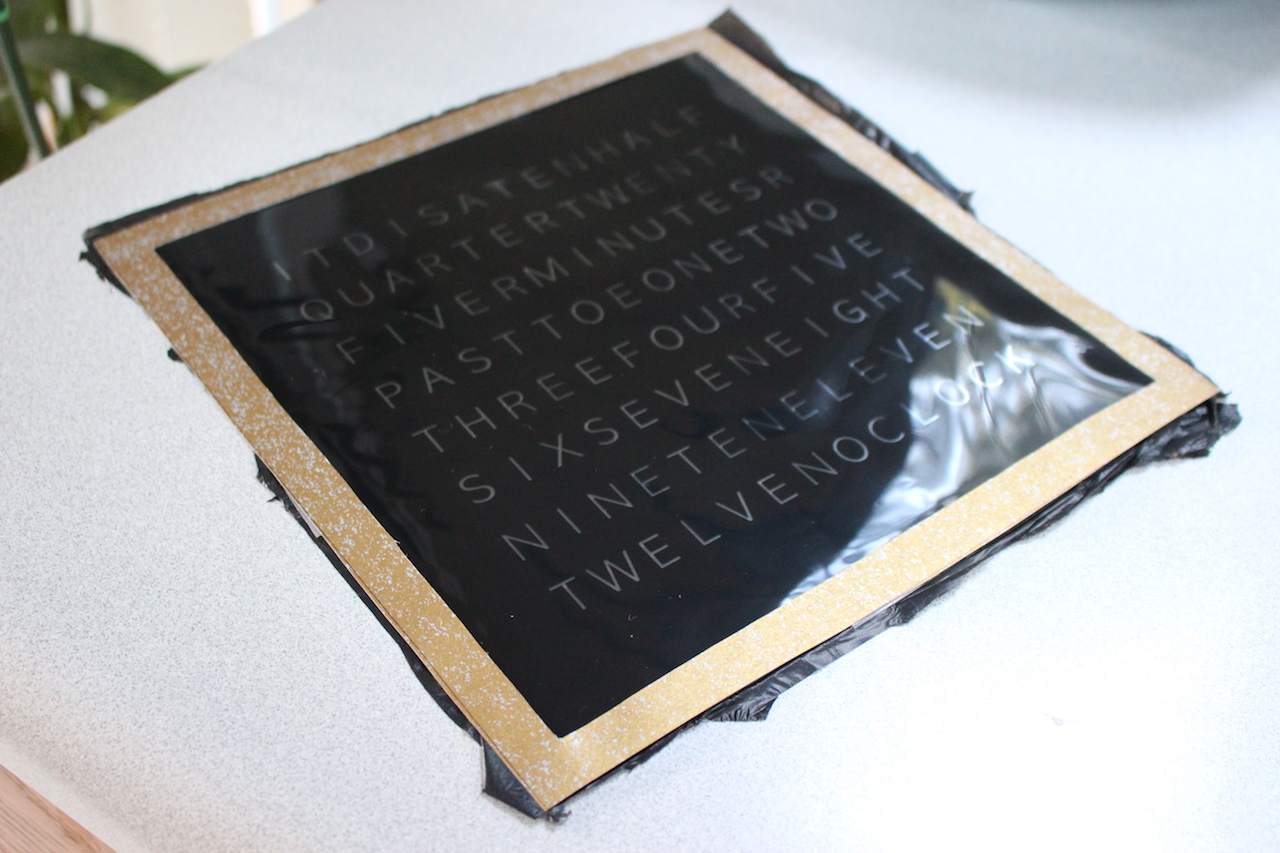

The letter mask is the clock’s face. It sits in front of an array of LEDs, transforming each one’s light into an individual letter.

I made a letter mask in GIMP sized around the chassis’ dimensions. I went with AppleGothic for a sleek look, and left some space around the edges for aesthetics and the non-LED electronics. I placed each letter of the mask in its own cell of a grid, effectively monospacing the font.

I had several copies printed out on transparencies at Kinko’s, cut three to fit, and carefully aligned and adhered them to each other using clamps and double-sided tape. The black ink isn’t perfectly opaque; stacking the sheets prevents light from bleeding through where it shouldn’t.

I cut a hollow rectangle out of amber construction paper and adhered it to the front of the transparencies. It provides some color, and closes openings in the shadow box’s viewable area. I attached a black garbage bag to the rear of the masks to diffuse the light coming from the LEDs, making the display directly viewable and consistently bright.

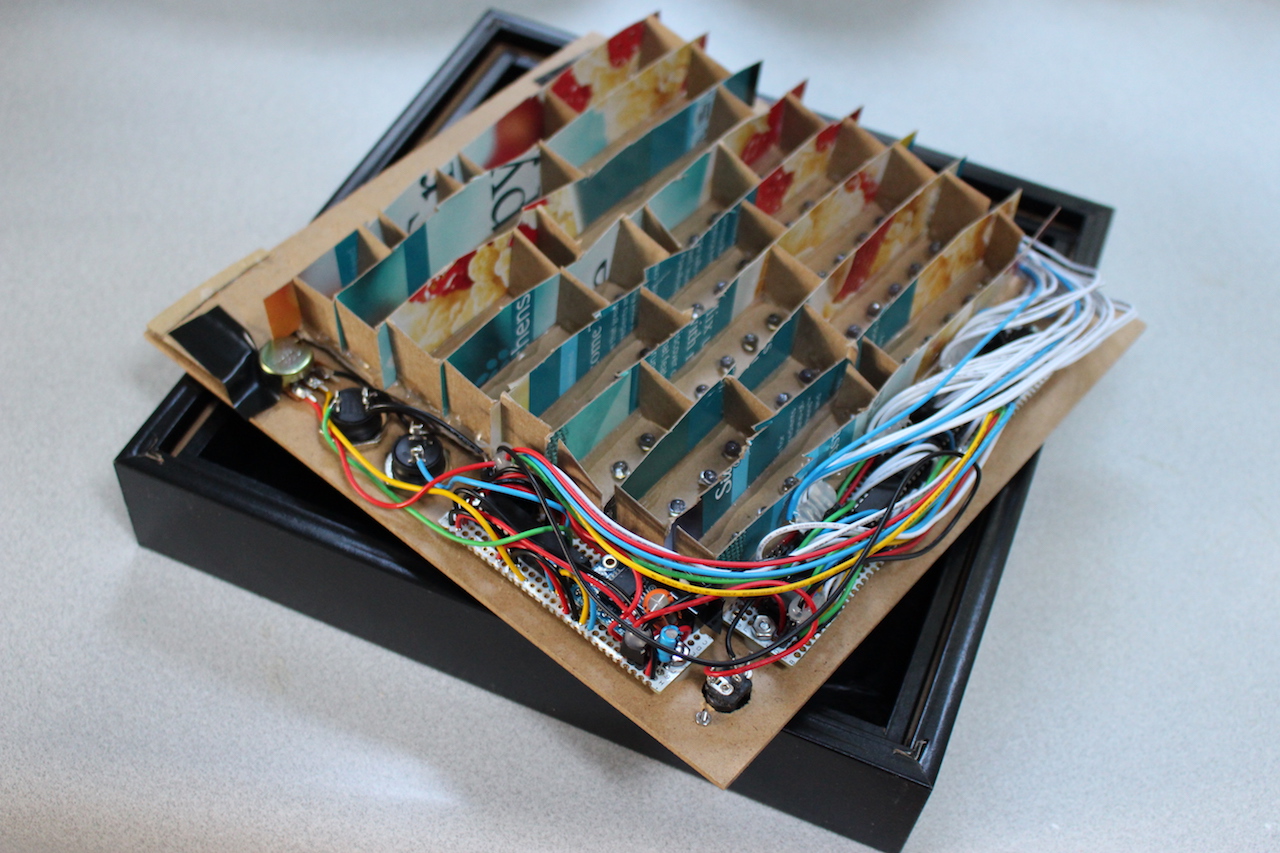

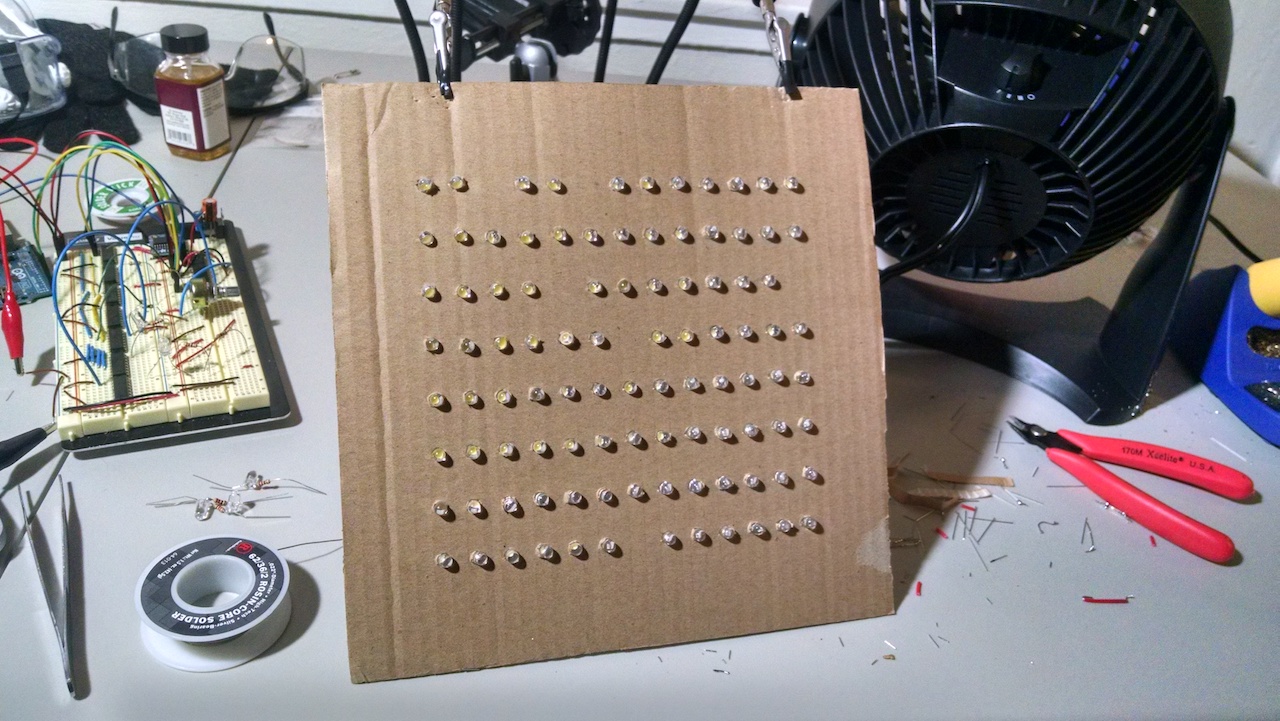

LED Array

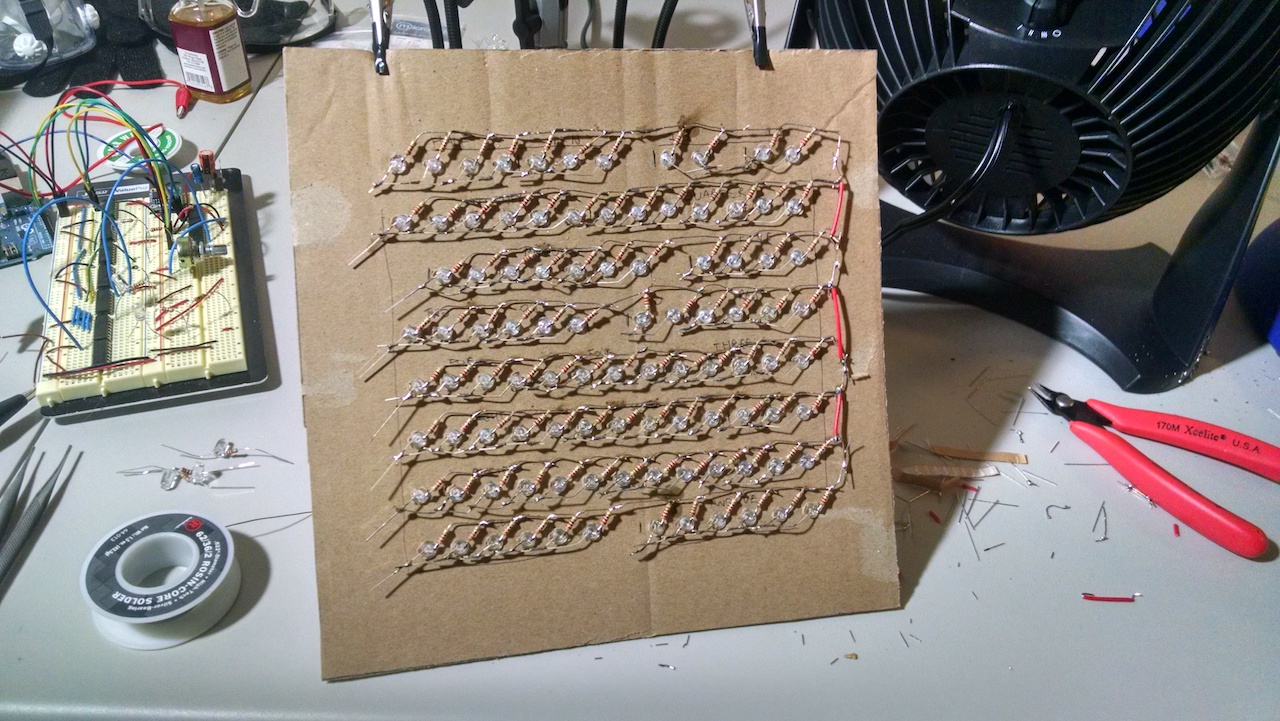

The LED array has 98 LEDs, each for an individual letter of the mask.

I made the LED array by punching a bunch of holes in a piece of cardboard. After soldering a resistor to the anode of each LED, I placed each LED in a hole and soldered each resistor to each other to provide a common power connection. I connected the cathodes of each word-forming group of letters to each other, and brought out a wire from each common cathode for connection to the driver board.

Later, I cut some baffles out of a cereal box and adhered them to the mask using hot glue. This minimizes inter-word light bleeding.

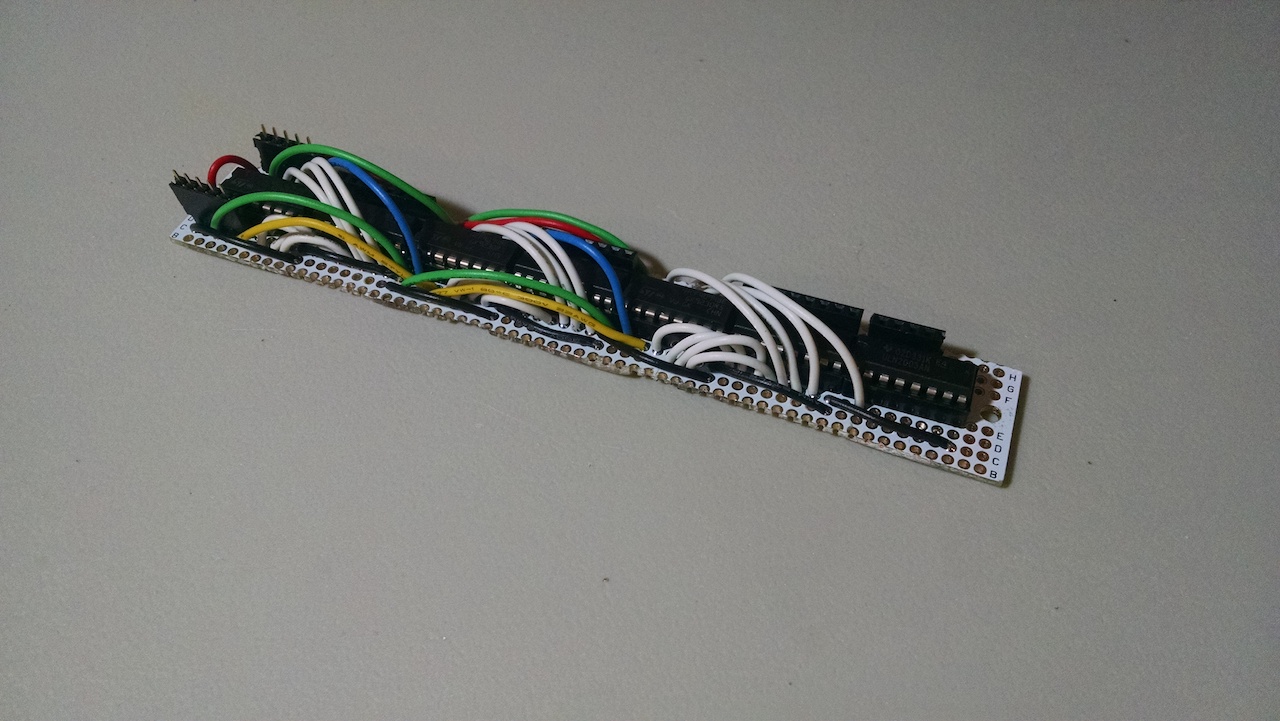

Driver Board

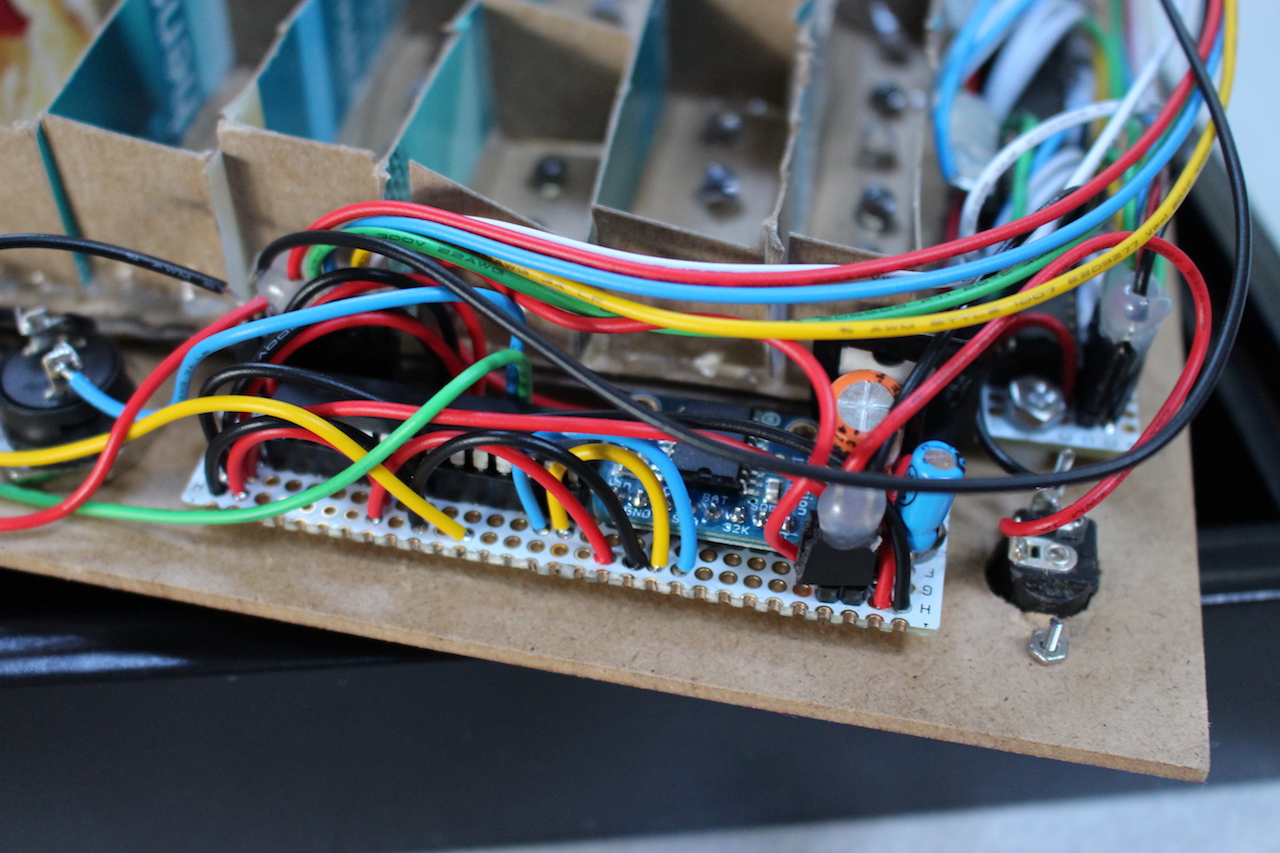

The driver board gates the ground connection of each word-forming LED group.

Each word sits in front of a Darlington transistor of a ULN2003A chip whose input is a bit of a logical 24-bit shift register formed by three 4094 chips. The 4094s get their register values from a separate control board. I borrowed Scott’s circuit and soldered this board by hand.

Control Board

The control board listens to the user interface, figures out the time of day, and controls which words the driver board lights up. I designed this circuit myself and soldered the board by hand.

Microcontroller

I chose an ATMega328P for the clock’s brain since I had a few lying around, and AVRs are easy to interface with thanks to the Arduino environment. That said, any chip with basic peripherals and a modest amount of memory - I2C, PWM, analog in, 16K ROM - would have been fine.

RTC

The MCU gets the time from a DS3231 RTC. I got one from Adafruit that’s wrapped up in a convenient eight-pin breakout and sports a coin cell battery backup. This backup means the time isn’t lost when the clock is unplugged, at least for 3 to 4 years - the RTC draws about 0.84μA in standby and the battery I picked supplies 38mAh.

The DS3231’s accuracy depends on its environment’s temperature. In the conditions of its paradisiacal southern California home, it’s accurate to a ±2 PPM window. In other words, for every million seconds of actual time that pass, the clock’s time will stray by at most two seconds in either direction. The clock will stray by no more than about a minute per year.

I considered another design that opted for an external crystal rather than an RTC. It would’ve saved on cost, but require custom time-calculating firmware, be less accurate, and a challenge to battery back.

Power

The clock draws from a 7.5V 1A wall adapter. That’s fed raw to the LED array, and regulated down to 5V for the control and driver boards. I chose 7.5V instead of 5V because I didn’t want too much variance in each LED’s brightness when accounting for resistance and diode forward voltage drop tolerances.

I was careful to pull down the driver board’s outputs, so that while the MCU is booting up the driver board won’t turn on all 98 LEDs simultaneously and overload the wall adapter. I picked out an adapter with a fuse just in case.

User Interface

The user interface has two buttons for time adjustment (hour advance and minute advance) and a potentiometer for brightness adjustment. I sized the buttons to accommodate my dad’s large fingers; he’s 6’5”. The potentiometer controls the output enable pins of the shift registers using PWM for a dimming effect.

Each interface component is panel-mounted to the rear of the shadow box. I hand drilled slots for each; a metric step bit was especially handy, since I didn’t have any metric bits coming into this project.

Firmware

After initializing each relevant pin, the firmware regularly polls the inputs and adjusts the RTC’s time and its output enable PWM pin width as appropriate. It periodically queries the RTC for the current time and updates the driver board’s shift registers every five minutes.

Firmware comes naturally to me now thanks to years of experience, so this project’s was pretty straightforward. The most fun I had here was deciding how the clock should respond to the user pressing its buttons. Since the clock is only precise within five minutes, should the minute advance move the time forward by one minute or by five? How long should a user have to hold a button before that button’s action is repeated, if ever, considering the target user? Should the clock reset its second counter when its time is advanced? I spent nearly as much time answering these questions as I did writing the rest of the code.

Gallery

Documents

Lessons Learned

- Source your components from reliable sellers on an as-needed basis. I used years-old LEDs purchased on eBay, and several were nonoperational before use. Several more burned out within a few hours of use and needed to be replaced. Desoldering isn’t as easy as soldering.

- Size your project components precisely given the chassis before designing anything. I sized the letter mask without properly accounting for the electronics boards that would sit behind it, and had to fit the boards in a really limited space. I had to hack up the perfboards and make some gross serial connections that could’ve been parallel.

- Review mechanical diagrams closely before purchasing components, and make sure you have the right tools to mount things. I made incorrect assumptions about the panel-mounted interface components and had to use some hacky drilling techniques to work around missing bit sizes and non-circular hole shapes. A laser cutter would have been lovely here.

- Consider designing and fabbing a PCB after proving out the circuit. This project had a ton of electrical connections, and I soldered it all by hand, and it was tedious. Especially the LED array. Your time is valuable, and your project could use the reliability!

- Try living with your creation for a while, if it’ll be a gift. Years later I still see this when I visit my parents, which is pretty cool, but then I think dang.. I totally should’ve made the words fade in and out when transitioning instead of having a hard cut.

Addendum

A few months after giving this as a gift, I received reports that a few more LEDs burned out. Instead of swapping them out, I took the opportunity to use what I learned to do better.

I dumped the circuit into Fritzing, routed it out to a monster 9”x9” board, and got it fabbed. Connecting the controls to the board was kinda jank, but soldering everything was way easier, and didn’t require miles of wire. I also used Cree LEDs instead of eBay ones. They’ve been going strong for four years. Even the IT IS letters, which have been on pretty much that entire time.

I probably still have the layout and Gerber files somewhere. No promises, but if you’re reading this and think they’d help, feel free to ping me. I’ll look for them.

Thanks for reading!